Discovering Black History – 18th Century Virginia

As a historical fiction writer, it’s important to research the era the story is set in to get a broad understanding of the customs, laws, beliefs and struggles of the people living in those times. My novel To Rescue a Witch and the soon-to-be-published prequel To Condemn a Witch have signification portions of the story set on a tobacco plantation in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Slavery is a worldwide stain that goes back millennium, of course so in this post I’m narrowing the focus to share some of the research I discovered specific to slavery in Virginia colony between 1730-1740. It includes links to websites, living history museums like Colonial Williamsburg, Shirley Plantation and Jamestown Settlement, and primary sources if you’d like to learn more about this aspect of American history.

Why Did Colonists Want Slaves?

Let’s start with some general information. The triangular trade fueled the 18th century economy. Europeans traded manufactured goods for captured Africans who were then sold to the Americas as slaves to work in the fields harvesting crops such as tobacco, cotton and corn. Many Africans ended up in Brazil, the West Indies and British colonies. The trip to North America was called middle passage and it was beyond brutal.

Slavery vs. Indentured Servitude

Slavery was similar to indentured servitude (another awful practice) but worse in some key ways. Indentured servitude meant a person was owned by a master for a fixed period of time and could eventually become free again. Sometimes a convict became an indentured servant as a way for the English crown to banish its unwanted citizens, knowing most would never be able to travel back when the sentence ended. Other times indentured service was a choice. For example, if you were starving in Ireland with no chance for advancement you might enter into an agreement where the master pays for your passage from Europe to Virginia and in exchange you work for them without pay for seven years. At the end of your contract you’d be granted your freedom and a small stipend, such as clothes, a plot of land or trade tools. Slavery, on the other hand, was a life sentence and the enslaved had no say in the matter. Slavery was also an inherited state, meaning once enslaved your children and future children were automatically enslaved too.

As noted, slavery was commonplace all over the world, but once it arrived in America it had a unique element: it slowly became based on race.

Slavery Comes to Virginia

In 1619 a Portuguese slave ship traveled to Mexico with a hull full of captured men, women and children from Angola, possibly from the Ndongo and Kongo kingdoms. What they could not have known was that more then half the captured people in the hull would die and two English pirate ships would overpower them and change the course of American history.

The surviving slaves were brought to Jamestown, an English settlement established twelve years earlier. According to the English colonist John Rolfe, the ship “brought not anything but 20 and odd Negroes, which the governor and cape merchant bought.” Tobacco was a newly established crop that was profitable, so it’s likely those original twenty Africans worked in the fields.

By the end of the Civil War the enslaved population grew to 10 million people across the United States.

Pictured above is Jamestown Settlement, a living history museum I visited that shows what the colony would have looked like in the 1600s. (They also had a lot of information about the Powhatan tribe, but that’s a blog post for another day.)

The Law

It’s bizarre to think of people owning people, which is why it is significant English law specifically dehumanized the enslaved and defined slaves as property, to be bought, sold, rented out, or mortgaged.

The idea that slavery was specifically tied to race evolved over time. For example, in 1656 Elizabeth Keys became the first person of African descent to sue for her freedom in court and win. Born in 1630 in Warwick County, Virginia, her mother was an enslaved African and her father was a white English farmer named Thomas Key. She was baptized but considered illegitimate and was put into indentured servitude to a judge named John Mottram and supposed to be freed at age 15. The judge also paid for passage some English servants, including a man named William Grinstead. Elizabeth and William fell in love and had a son. The judge then died. His heirs said that they now owned Elizabeth and her son because they were Black. By this point, William completed his indentured service, was a free man… and a lawyer. He sued for Elizabeth and his son to be free for a number of reasons, but the main one was that her father was a white man, and according to English law the state of a person’s bondage followed the father. Ultimately she won the case and her freedom.

But.

The elites changed the laws to ensure it worked for their benefit. Specifically, for Black people a person’s state of bondage followed the mother instead of the father, thus every child she had was born enslaved. One could argue this legal change essentially encouraged rape because the owner increased his profits by having more slave labor and faced no legal consequences for doing it.

The updated Virginia Slave Code of 1705 grew more restrictive. Among other things, it allowed masters to kill slaves without penalty, denied slaves the right to own weapons or move without written permission and forbid all slaves or even free Blacks to assault white people. The characters in my story would have been living under these laws.

Running to Freedom

Since slavery was a life sentence and the ability to purchase your freedom was rare and difficult, the default to motivate enslaved people was violence. Movies often depict whippings and the tortured reality is worse. I will list some resources at the end if you’d like to read more about it.

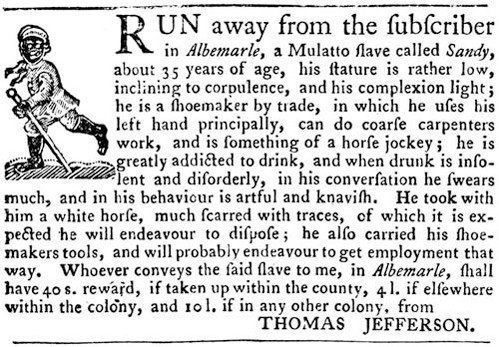

I read dozens of newspaper ads for runaway slaves. When they give physical descriptions you soon see how scars were common on their faces, arms, over their eyes. It was also jarring to read ads where the master was a minister, not something I expected. The ads, while in the perspective of the owner, do offer insight into what enslaved people wore, their age, what they felt important enough to take when they escaped, and the value the owner placed on them. The Yale Slavery and Abolition Portal has a ton of information from biographies, to deeds and insurance policies, to revolts and rebellions. This ad blew me away when I realized who wrote it…